Men & Solitude: 12 BOOKS

Here are shorter reviews of books by men recounting solitude experiences -- existential, not theoretical. That the authors are men suggests interesting psychological revelations, but perhaps not. All contain general reflections on their pursuit of solitude.

Richard Byrd - Jon Krakauer - Michael Finkel

Howard Axelrod - Jon Katz - Richard Mahler

Deep Country: Five Years in the Welsh Hills, by

Neil Ansell. London: Hamish Hamilton, 2011.

Deep Country: Five Years in the Welsh Hills, by

Neil Ansell. London: Hamish Hamilton, 2011.

Deep Country plunges the reader without ceremony directly into the silence and solitude in which Ansell dwelt for years. This depth of solitude is the book's co-author, a palpable presence. The writing is Thoreau without chattiness, Muir without ecstatics, wilderness without adventurism, a strong undercurrent of both confidence and stoicism.

Ansell lived alone in Penlan Cottage for five years, summer and winter, with no car, phone, clock, fossil fuel, or mirror, in "a place so remote that you may not see another soul for weeks on end." The book is about himself -- though he is imminently observant while self-effacing -- about his routines, but especially about "the wild creatures that became my society."

Ansell hints of earlier solo treks and travels, and modest support for the bird surveys he pursues; details about birds reflect a solid ornithology, but all sorts of creatures pass through the pages. Ansell grows food and forages. "I had a daily routine dictated by the simplicity of my lifestyle, and an annual routine too, led by the seasons, the elements." The reader shadows Ansell meticulously, unwittingly curious about the day's events, but knowing that they are not of their own but part of the palpable solitude of nature.

Ansell does muse on what anyone else would have discovered about

themselves given five years "free of social obligations, free of work

commitments ... all that time to consider your past and the choices you

had made, to focus on your personal development, to know yourself

through and through, to work out your goals in life, your true

ambitions." But none of this happened to him, for he immersed himself

into everything, especially into nature, developing a keen awareness

and attentiveness, while indoors focusing on his routines and staring

primordially at his log fire when chores were done.

The silence outside was reflected by a growing silence within. Any interior monologue quietened to a whisper, then faded away entirely. I have never practised meditation, but there is a goal in Buddhist practice of achieving a condition of no-mind, a state of being free of thought, and I seemed to have found my way there aby accident. I certainly learned to be at ease with myself in the years I spent at Penlan, but it was not by knowing myself better -- it was by forgetting I was there. I had become a part of the landscape, a stone.

Why only five years (from 1990-95)? Ansell developed de Quervain's

thyroiditis (not described in detail in the book), which may have been

caused by exposure to a virus carried by bats or mice or their

droppings (in or near the cottage). This ending makes for a solitary's

caution. After a medical regime he is well. Plus he married.

reviewed 2014 ¶

Jack Kerouac (1922-1969) was an unlikely candidate for an experiment in solitude, but he undertook a sixty-three day stint as a fire look-out on Desolation Peak, in the Cascade Mountains of Washington State. His life had been a zigzag from aloneness to social frenzy for years, and at the time of the experiment, the famous books that were to confirm his place in American literature epitomizing the Beat Generation of the 1950's still remained unpublished. The winding trail of drugs, alcohol, sex, homelessness, vagabonding, in-group, and incessant reading and writing was beginning to unravel into despair. In 1954, Kerouac took up the study of Buddhism as a possible solace. But as his friend Joyce Johnson has perceptively written:

Although Kerouac would achieve a deep intellectual understanding of Buddhism and would learn to practice meditation, his pursuit of peace had a frantic quality that was self-defeating. Through Buddhism, he could rationalize the void he had discovered within himself, but he could never really accept it.

On the advice of Gary Snyder, the poet-scholar-translator-roughneck who had worked as a fire look-out himself, Kerouac applied and was accepted to work during the summer of 1956. He spent sixty-three days on Desolation Peak with, as he put it, "no characters, alone, isolated." The record of this period is the first part of his novel Desolation Angels, entitled Desolation in Solitude, plus a little of the second part. Since all of Kerouac's fiction is literal autobiography, these passages can be taken as a reliable reflection of his thought at the time.

There are evocative passages in Desolation in Solitude, but everything is run through his jocular, cynical, compulsive, subjective persona. Here is a typical passage:

The Void is the crystal ball itself and all my woes the Lankavatara Scripture hairnet of fools, "Look sirs, a marvelous sad hairnet" -- Hold together, Jack, past through everything, and everything is one dream, one appearance, one flash, one sad eye, one crystal lucid mystery, one word -- Hold still man, regain your love of life and go down from this mountain and simply be--be--be the infinite fertilities of the one mind of infinity, making no comments, complaints, criticisms, appraisals, avowals, sayings, shooting stars of thoughts, just flow, flow, be you all, be you what is, it is only what it always is -- Hope is a word like a snow drift -- This is the Great Knowing, this is the Awakening, this is Voidness -- So shut up, live, travel, adventure, bless and don't be sorry ...

Most of his days Kerouac passed in conjuring memories, fantasizing, counting the days until he could return to San Francisco, return to normalcy, which was the endless rounds of drinking, eating, talking, staring at life as a spectacle.

In finer moments, Kerouac talks about the Peak's snow, trails, a caterpillar, picking wild blueberries, and confesses to murdering a mouse. He talks about the mind, the dusk, radio chatter from other look-outs, a storm, and occasional references to the famous Chinese mountain hermit, icon of the Beat circle, Han-shan:

I called Han Shan in the fog -- there was no answer--

The sound of silence

-- is all the instruction you'll get.

Kerouac was busy writing haikus in this period, and a number first appear in Desolation Angels.

Though we cannot not dispel his cleverness and zest for life, the pathos of Kerouac is transparent. The experiment in solitude was grist for a writer's mill, involuntary but pragmatically useful, like everything else Kerouac touched. But the sadness is palpable.

Desolation Adventure finds me finding at the bottom of myself abysmal nothingness worse than that no illusion even -- my mind's in rags.

Returning to San Francisco, he offers this conclusion:

The vision of the freedom of eternity which I saw and which all wilderness hermitage saints have seen, is of little use in cities and warring societies such as we have.

The following year (1957) Kerouac finally published On the Road

and Dharma Bums the year after that -- and so the legendary

chronicler of the Beat Generation was established in history. But

though he published regularly after that, Kerouac's self-destruction

spun unchecked and in growing solitariness until his death in 1969 at

the age of forty-seven.

reviewed 2008 ¶

Edward Abbey's chronicle of a year's stint as park ranger in Arches National Park near Moab, Utah, as caretaker of what Abbey calls a "33,000-acre garden," is a brilliant tour-de-force revealing every nuance of its author's strong personality and of the magnificent desert environment he encountered.

Abbey has an encyclopedic knowledge of plants, rocks, animal life, meteorological lore. His unabashed love of wilderness and its preservation rivals that of his heroes Muir, Thoreau, Audubon, Catlin the painter, and John Wesley Powell, the one-armed explorer-adventurer. Every page is filled by Abbey's opinionated, garrulous, sardonic, sensitive voice, yet it is isolation, solitude, and silence that awe him.

I am here [in the wilderness] not only to evade for a while the clamor and filth and confusion of the cultural but also to confront, immediately and directly if it's possible, the bare bones of existence, the elemental and fundamental, which sustains us. I want to be able to look at and into a juniper tree, a piece of quartz, a vulture, a spider, and see it as it is in itself, devoid of all humanly ascribed qualities, anti-Kantian, even the categories of scientific description. To meet God or Medusa face to face, even if it means risking everything human in myself. I dream of a hard and brutal mysticism in which the naked self merges with a non-human world and yet somehow survives still intact, individual, separate.

The year (minus winter) includes rich first-hand accounts of desert flora, snakes, water, rocks, heat, rivers, a feral horse. Abbey spends the hours alone, occasionally finding a taciturn buddy for climbing or river-rafting, but pursuing a lot of daredevil adventuring alone. He offers splendid polemics against anything that threatens nature and wilderness.

There is no desert spirituality or eremitic journal-keeping here. Abbey is too ornery, too rough-and-tumble a character for that. For all his bravado and exploits, though, Abbey keeps his sentiments close.

Desert Solitaire, now a virtual classic, is a unique

documentation of one man's embrace of solitude, wilderness, and

what Abbey calls the "delirious exhilaration of independence."

reviewed 2006 ¶

Solitude:

Seeking Wisdom in Extremes - A Year Alone in the Patagonia Wilderness,

by Robert Kull. Novato, Calif.: New World Library, 2008.

Solitude:

Seeking Wisdom in Extremes - A Year Alone in the Patagonia Wilderness,

by Robert Kull. Novato, Calif.: New World Library, 2008.

Kull spent a year in solitude on a tiny isolated southern Chilean island facing sea and mountains, in part as an unusual academic exercise to fulfill PhD requirements, and in part because he has spent a lifetime pursuing adventure and self, holding odd jobs and plunging into wilderness and retreat situations. The book is a meticulous daily narrative of twelve months (February 2001 to February 2002) taken from his journal, with monthly interludes to organize recurring themes, plus a few appendixes.

This book represents a breakthrough. Analogies with Thoreau or Edward Abbey are not wrong in trying to identify the unique mix of wilderness survivalism with philosophical reflection, but those authors represent 19th and 20th century themes respectively. Kull embarks on the cusp of a new century and strikes a post-modern tone.

While the narrative engages the quantifier interested in details of camp, motors, tools, shelter, food, boats, and nature, the philosophical and psychological ruminating is what really marks the book as unique, distinct from Kull's many predecessors in the wild. Kull is observing an analysand, namely himself, opening lids to Pandora boxes of self and unconscious, with solitude as a tool, a context, and a balm.

At first glance the 300-plus pages are intimidating. But the daily journal (some days have no entry) lures the reader into following every possibility of wilderness solitude. The thinking aloud and the organizing interludes give character to the prose. Kull is brutally straightforward in self-analysis, telling us about his life, traumas, fears, habits, failures, and hopes.

Solitude exorcises ghosts -- or at least brings them to the surface. Kull knows this from Buddhist and previous wilderness retreats. But in this extended wilderness solitude he is free in mind and body to explore all possibilities that the unconscious wells up. To pursue this catharsis takes courage, but to do this in the fascinating natural setting he has simultaneously edged into cautiously as well as thrown himself into boldly, makes the book a grand testimony to what is possible for anyone who attempts to reconcile both physical solitude and spiritual solitude. And Kull was 55 when he did it!

As for readers looking for pictures (the book has none, probably to keep down the cost), Kull's website photo gallery and post-year video round out the journey.

Everything is here, and the variety is engagingly real and present, though the meticulousness may have been reserved for his academic exercise as much as for the casual reader. Kull's journal deftly shifts from reactions to the books he is reading, to observations of how the sound of rain and flow of sea affect the mind, to core themes of Buddhism and meditation, to tinkering with the unpredictable boat motors, to what he eats, to making sense of his past, to observations about ducks, dolphins, nutria, and limpets. Sometimes he wonders if he should write at all, writing appearing to be an escape from true solitude.

Does it all work? Did the year bring new revelations, solutions to problems, wisdom in extremes? Kull had prepared himself with solid resources, both for survival and for journaling and reflecting. He was often surprised, overwhelmed, ambivalent, torn between missing people, realizing what harm his past has done to many, and reconciling himself to a psychological solitude. Disciplining himself in these wilds with hours of daily meditation, Kull sought to allow small mind to glimpse big mind. What stands out is the self-examination, the openness to self-confession. The search for solitude is the search for solace, and as Kull puts it in the preface:

Most stories have a beginning, middle, and end, and they draw us into some other time and place. This story is different: it's all middle -- no clear beginning, no definite end -- and it slips out of time and into the eternal now. It's a journey into one of the most remote places on the planet and into some of the darkest recesses and brightest openings of the human spirit.

Robert Kull is a unique voice pursuing the complexity of solitude and self. His book is a very welcome addition to the experience.

reviewed 2008 ¶

The "hermit" of the title is the author, who has traveled to the Indian Himalayas on a solitary respite in a mountain bungalow. Addressing his Western critics who want him to stay visibly busy, he says:

I have become an idler, useless to society and unprofitable to myself, a do-nothing who merely sits still and endeavours to keep away the waves of invading though that advance upon him. In short, I possess neither fixed status nor recognized place in the world. I an no longer respectable. Does it matter?

But does he mean it? Paul Brunton (1898-1981), journalist of the spiritual and esoteric, travel writer, and popularizer, was not a hermit, though in this book he plays at one. That is not necessarily offensive -- who can claim to be a pure hermit? -- but Brunton can be too flippant at times, as when he refers to the mail-carrier:

To me he is a valued necessity for he keeps open my line of communication with the outer world. Such a service might well have been scornfully disdained by the ancient or mediaeval hermits, but to a twentieth-century hermit like myself it is a welcome one. Modern habits for modern hermits is my slogan. ... Thus I live secluded but not isolated.

Or when he reflects on his appearance before his servant, priding himself for not wearing "a starched uncomfortable shirt for dinner" but notes that he does shave every day. "A beard, however, would be quite fitting to a hermit, but I fear to go as far as that."

The book has the whiff of Old World patronizing and lack of depth about what the East really is. In part it is the era of the thirties: too old to learn, too new to be humble, characteristic of similar books by Western apologists in those days.

Brunton is rightly famous for having introduced Ramana Maharshi to the West in his 1934 book, A Search in Secret India. His other books, up to when Brunton stopped publishing in 1952, have earned a small but loyal following. Brunton's writings express the generic style of New Thought and Theosophy. "I have found no mooring for my floating soul in any religious faith, in any philosophy," he notes in A Hermit in the Himalayas, "because I believe in the Spirit which, like the wind, bloweth where it listeth."

But Brunton lacked the flamboyance of Blavatsky, the doggedness of Alexandra David-Neel, the roguishness of Gurdjieff, the imagination of Ouspensky. His work reflects the now dated assumption that association with the East meant a non-descript occultism, a spirituality gained by osmosis, not by study, meditation, or self-discipline (though he pooh-poohs reincarnation and astrology). On solitude, Brunton is rather pointed:

Use solitude but do not abuse it. ... I believe in rhythm, in withdrawal only if followed by activity, in solitude only if followed by society, in self-centered development only if social service is its later complement, in spirituality only if nicely balanced by materiality.

And:

Asceticism is not attractive to the modern man. My belief is that it is also not essential.

Yet Brunton enjoys the atmosphere of the spiritual and religious. He loves Krishna, Buddha, Jesus -- but speaks more of God the Creator than of his occasional references to Masters of Light and the Overself. Perhaps he doesn't have much original to say in that regard, even less on what it means to be a hermit and what is solitude. Brunton has made of his solitary retreat a book, not a book of practice or advice but a garrulous romp by a seasoned travel journalist who cannot help but be chatty. A Hermit in the Himalayas belies its attractive title. Interestingly, it is seldom referred to by those who still follow Brunton closely.

reviewed 2009 ¶

Alone, by

Richard Byrd; New York: Putnam, 1938

(first) Washington, DC: Island Press, 2003 (latest)

Alone, by

Richard Byrd; New York: Putnam, 1938

(first) Washington, DC: Island Press, 2003 (latest)

As a military officer, Rear Admiral Richard E. Byrd (1888-1957) of the U.S. Navy had no interest in solitude except as a practical condition of athletic prowess or technological achievement, having attempted to fly across the North Pole in 1926, fly non-stop across the Atlantic Ocean in 1927, and having endured five months of winter in an Antarctic base camp in 1934, the subject of his autobiography, Alone.

A streak of stubborn ego may have dogged Byrd, who falsified his North Pole flight claim, lost his bid to lead the first trans-Atlantic non-stop flight to rival Lindbergh, and refused the help of others when nearly dying of carbon monoxide poisoning while alone in the remote Antarctic camp at Bolling Advance Weather Base, nicknamed "Little America."

Due to technical circumstances, Byrd, as base commander supervising various weather-related data, had to decide: "I had to choose whether to give up the Base entirely -- and the scientific mission with it -- or to man it by myself. I could not bring myself to give it up." He owned that the psychological risks were "real" and distinguished his isolation from true solitude, contrasting Thoreau's deliberateness to Robinson Crusoe's inventiveness, the latter more like himself.

Byrd meticulously catalogs the provisions left to him, from fuel to food, and describes his little quarters without misgivings as a span of four strides one way and three strides the other, with the dimness to his liking. He maintains a regular schedule of surfacing to take weather readings. At below 50 degrees Fahrenheit, strange things happen: kerosene freezes, Novocain freezes, cold destroys skin and tissue, silence descends, darkness permeates. Yet Byrd feels an exhilaration, and says that now he understands what Thoreau meant of the body feeling all sentient, for Byrd, too, is emptied of thought and given over to the slightest sensations, sounds, and feelings in such a setting.

There are wonderful passages in the early chapters covering April and May 1934, such as:

I felt as though I had been plumped upon another planet or into another geologic horizon of which man had no knowledge or memory. And yet, I thought at the time it was very good for me; I was learning what the philosophers have long been harping on -- that a man can live profoundly without masses of things. For all my realism and skepticism there came over me, too powerfully to be denied, that exalted sense of identification -- of oneness -- with the outer world which is partly mystical but also certainty. ...

It was exhilarating to stand on the Barrier and contemplate the sky and luxuriate in a beauty I did not aspire to possess. In the presence of such beauty we are lifted above natural crassness. And it was a fine thing, too, to surrender to the illusion of intellectual disembodiment, to feel the mind go voyaging through space as smoothly and felicitously as it passes through the objects of its reflections. The body stood still, but the mind was free. It could travel the universe with the audacious mobility of a Wellsian time-space machine. ...

The universe is an almost untouched reservoir of significance and value, and man need not be discouraged because he cannot fathom it. His view of life is no more than a flash in time. The details and distractions are infinite. It is only natural, therefore, that we should never see the picture whole. But the universal goal -- the attainment of harmony -- is apparent. The very act of perceiving this goal and striving constantly toward it does much in itself to bring us closer, and therefore, becomes an end in itself.

But then come the effects of carbon monoxide fumes: bouts of fear, depression, apathy, weak limbs, blurry thinking, hunger and thirst in his inability to move, to keep down food if he can reach it, sleeping hours on end -- nearly a death sentence. How Byrd manages through these excruciations, fending off the suspicions of his off-site crew awaiting his daily telegraphic check-ins, is an adventure tale that entertains but also offers a cautionary warning about the limits of survivalist projects and extremes of self and bravado.

reviewed 2010 ¶

Into the Wild, by Jon Krakauer; New York: Villard, 1996; Anchor Books, 1997.

Jon Krakauer's account of the life and demise of Christopher Johnson McCandless is a cautionary tale for anyone contemplating wilderness solitude. The journalist author offers up sufficient detail to present the enigma of the young rebel whose haunting photograph of himself in his last days clearly reveals a dying man. Krakauer is an accomplished outdoor enthusiast and a seasoned climber familiar with wilderness survival. He first broke the McCandless story in Outside magazine shortly after the discovery of McCandlesss' death in 1993. Krakauer then pursued meticulous research into the life and circumstances of the young adventurer.

This combination of solid journalistic skills and thorough experience with wilderness settings is essential in approximating the psychology of McCandless. The book interprets the story to an audience that may not understand wilderness and the motive of solitude. This element is absent in the film and video of the same title, which is accurate in its facts and very poignant in its last scenes, but does not (nor can it) carry the insightful reflections, analysis, and anecdotes of the book, especially not the literary inspirations of McCandeless that give us a clue to his youthful but heartfelt quest for identity.

McCandeless was a paradox: socially-engaging, he could withdraw from interpersonal relations without regret; one of the closer people he encountered recalled that

"He had a good time when he was around people, a real good time. ... He needed his solitude at times, but he wasn't a hermit." He was a paradox wherein both academics and the outdoors were equally easy arenas for accomplishment. Well-born and well-educated, he was willing to throw away structure and social success to live as a penniless wanderer. As he wrote to the elderly Ron Frantz:

"So many people live within unhappy circumstances and yet will not take the initiative to change their situation because they are conditioned to a life of security, conformity, and conservatism, all of which may appear to give one peace of mind, but in reality nothing is more damaging to the adventurous spirit within a man than a secure future. The very basic core of life comes from our encounters with new experiences, and hence there is no greater joy than to have an endlessly changing horizon, for each day to have a new and different sun. ... You are wrong to think Joy emanates only or principally from human relationships. God has placed it all around us. It is in everything and anything we might experience. We just have to have the courage to turn against our habitual lifestyle and engage in unconventional living."

McCandeless' deep reflection on Thoreau, Tolstoy, Jack London and others has been dismissed as idle fantasy, but in the heat of youth, McCandeless conceived of integrity and honesty as paramount in finding self-identity and a sense of ethics in a world gone mad. And in the end, he did survive the time he had allotted himself to his Alaska adventure: one hundred days. And in the end, too, he simply made honest mistakes that could not be reversed because of his earlier brashness: his refusal to leave a trail of his whereabouts, his refusal to equip himself well in clothing, tools, maps, and compass, his refusal to soften the hardships of solitude.

Krakauer performs an excellent service in both pointing to deficiencies in surveying the history of young men who refused to taken necessary precautions, but sympathetically trying to recreate their mindset. It is not so much a matter of belittling a McCandeless arrogance and ignorance, as have many Alaskan outdoorsmen, even to the point of calling him suicidal. The challenge is to try to understand the nuances of a fundamental drive in young survivalists, extreme sports enthusiasts, and driven idealists and solitaries. We may suspect that the drive is a universal one that simply manifests itself in different ways in different people, including the McCandless critics. Understanding the many forces that shaped McCandless -- psychological, emotional, social, intellectual, cultural -- is to better approximate not only the makings of this one young man but in varying degrees all of us.

reviewed 2008 ¶

Journalist Michael Finkel employs his knack for narrative nonfiction to tell the story of Christopher Knight, the "North Pond hermit" of Maine who, for nearly thirty years, survived alone in a forest close to an encampment of tourist cabins, from which he regularly stole food and supplies to successfully maintain his concealment. The tale tumbles by in a breezy and readable style, but leaving a human enigma to ponder.

Finkel kindly credits the Hermitary website for its "invaluable resources" for researching his subject and preparing to encounter Knight. But was Knight really a "hermit," let alone the "last true" hermit? Finkel acknowledges that on the Hermitary website, most participants on a then-active forum opined "no."

Not that this debate is new. In the Western world, hermits evolved under church tutelage, expected to adhere to a specific monastery and to the abbot's authority. But social and economic conditions in the early Middle Ages created rampant hardship and pauperism leading to displaced and homeless men turned wanderers and thieves. How to distinguish hermits from criminals? And where would Knight have fit with his unclear psychology?

St. Augustine called them circumcelliones, those going round and round, and several synods of the era condemned religiosi vagabondi. St. Benedict, who essentially codified monastic practice in the West, called hermits not under church control sarabaites and gyrovagues, basically wanderers, individually or in groups, all of whom he presumed lived off of alms or thievery. This suspicion of hermit motives was to last not only through the Middle Ages, but thereafter, secularized for modern criminal and penal codes and sensibilities.

This attitude contrasts with Eastern views of hermits, where hermits were known for their strong ethical motives, and wandering was inspired by eremitic religion or philosophy, whether Hindu, Taoist, or Buddhist.

Hermits and eccentrics have always been objects of curiosity in American popular culture. Carl Sifakis identified over forty "eccentrics" over three centuries and Marlin Bressi cataloged over eighty "hermits," variously called wild men, mountain men, and cave-dwellers, Bressi carefully distinguishing his hermits from recluses and misanthropes, noting that hermits do not fear society but simply prefer solitude.

Back to Christopher Knight. He certainly preferred solitude but was clearly wary of people. He stole everything from propane tanks and batteries to junk food, clothing, and winter gear. He never lit fires nor used lights at night. He did not rob but stole, deliberately avoiding encounters with anyone, although many cabin-dwellers felt terrorized, unsure what the stealthy burglar might do next. He never ventured farther than his tent and the vacant cabins. He read books (stolen) but did not write. Some doubt his survivability in winter, his ability to so conceal his presence, and his mental steadfastness.

Finkel's description of Knight suggests a decided place on the autism spectrum, but that is another story. After capture, Knight acknowledged the perfidy of his robberies, thus leaving his nearly thirty years of solitary life in moral ambiguity. The whole question of how to be a hermit in the modern world persists, unresolved and unmuddied by Knight's effort. By a generous standard, Christopher Knight will be called a "hermit," because that title redeems his enormous and ill-fated project. Perhaps the publisher insisted on the other appellations, for Knight the hermit is probably not the "last" nor the "true."

reviewed 2019 ¶

The Point of

Vanishing: A Memoir

of Two Years in Solitude, by Howard Axelrod.

Boston: Beacon

Press, 2015.

Seekers of solitude have been motivated by religion, philosophy,

love of wilderness, and plain self-perception of their status as

psychological outcasts,

plus a few jilted romantics, the last often literary recluses, not

hermits. Axelrod's quest for solitude resulted from

an accident: blindness in one eye resulting from a sports injury that

left the third-year Harvard student rethinking life

priorities, reassessing the future and his self-identity. He ends up

spending two years in an isolated off-grid northern Vermont house --

though not before a year in Italy resulting in a failed romance.

The

author writes deftly but his embrace of solitude eludes

articulated motive -- though the reader can reconstruct the

mental and emotional circumstances. At one point Axelrod tells his

brother that he can't really explain his

attraction to solitude experience, and when an old buddy demands to

know

the

"takeaway" when the author returns after two years have elapsed, the

author

cannot really say. Axelrod's details about monocular blindness are

intriguing -- one thinks of Oliver Sacks. His depictions of nature

in his solitary vicinity, especially during winter, are modestly

descriptive, and the anecdotes about the handful of people he

encounters seem ancillary. At least one person in his Boston social

circle alludes to Axelrod's

lack of preparation and planning by referring ominously to Chris

McCandless. The author was frequently sick, poorly nourished, and

unfamiliar with the climate and necessary gear and winter precautions.

Though writing many years after the incidents, the reader

senses that the author has not fully worked out the dimensions of his

solitude experience.

reviewed 2015 ¶

The Stars in Our Pockets: Getting Lost and Sometimes Found in the Digital Age, by Howard Axelrod.

Boston: Beacon Press, 2020.

In his first book, The Point of Vanishing, Axelrod set out his life circumstances: Harvard junior, grade A student, with loving family and doting friends. A pick-up basketball game with dorm buddies. Then a freak accident leaves Axelrod blind in one eye. The result was a subtle erosion of self-perception, of space and time and purpose, the overthrowal of contentment and convention culminating in his two-year solitude in the wilderness woods of northern Vermont, without television, radio, computer, and a telephone line seldom used. Axelrod discovers the pace of nature, the silence of snowfall in isolation, the pattern of stars in the sky. Awkward and unproductive encounters with villagers leaves him uncertain and reflective. Axelrod returned to compose The Point of Vanishing, thoughtful, reflective, and empathetic.

A few years later Axelrod consciously pens a sequel seeking a forum to explore themes of self, society, consciousness of time and place, trying to find meaning within what psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi describes in his book Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience. Axelrod is animated by a now-familiar peevishness about modern technology and social media as lamentable purveyors of alienation and social atomization, especially the ubiquitous cell phone. The author offers comments about William James and Csikszentmihalyi. He begins to approach his desire to refine communication, especially of what his accident revealed, that is not identical to what conventional thought and reflection can discover. Not experience but our interpretation is priority, according to Csiszentmihalyi.

But this supersession can militate against the experience of solitude and the derivation of lessons from the experience. Axelrod is forced to both demonstrate the lessons from his experience of two years of solitude and explain the conclusions to the people around him. Can it be fully expressed without embracing solitude as, after all, “optimal experience,” versus reconciliation to the world, to society? The author’s ruminatipns on these outcomes are sincere and thoughtful. He tells us that with “old friends kind enough to include a former hermit in their social circles, conversation didn’t come easily. … Small talk was a buzzing four-laned highway … nearly everyone wanted the bottom-line.” Namely, the bottom line on what Axelrod had learned in those two years in solitude. He was himself still working on that. “Without the comfort of those windows to the woods, I wanted … to carry some of what I’d felt on the roof in Vermont into the conversation. But i had no takeaway to offer. Maybe something about how I couldn’t squeeze the stars into a sentence or condense experience into a bottomline. But that answer wasn’t likely to fit the size of the conversational box being offered.” (p. 130)

reviewed 2024 ¶

Running to the Mountain: A Journey of Faith and Change, by Jon Katz. New York: Villard, 1999.

Jon Katz, a self-described hack television producer and mystery novelist, offers this book as a testimony to an episode of searching for solitude, using Thomas Merton as his model.

The book fails (painfully) because Katz clearly has no interest in solitude or, really, in Merton. They are props to his annual book-for-pay. He is turning fifty, in mid-life crisis, as he freely admits. Despite wife, daughter, comfortable suburban home and a mountain of debts -- but not the mountain of the title -- he buys a cabin in upstate New York for his experiment in solitude. A few months off to find himself.

But Katz's "solitude" consists of two dogs, a supply of Scotch, CD player, satellite dish and television, cell phone, and books by Merton and H. L. Mencken. He chatters incessantly with townsfolk, buddies, realtor, repairmen, people at the diner, the donut shop, the hardware store, wife, and even the ghost of Merton, who, however, does not appear until the last third of the book. He throws a few punches at Merton's familiar foibles, gloats a bit, slaps Merton's shoulder, and basically quits the experiment in a mix of triumph and homesickness.

Katz lacks what many people lack when the subject of solitude is brought up: humility, simplicity, and the will to disengage. But the lack of will to follow through with his inkling of solitude is worsened by mocking the effort with a contrived tour de force and a book to boot. Katz's family has enormous indulgence but readers will probably have very little.

reviewed 2005 ¶

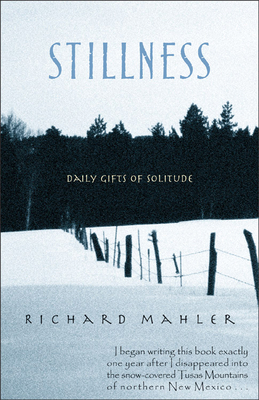

Stillness: Daily Gifts of Solitude, by Richard Mahler. Boston: Redwheel, 2003.

The publisher lists this book as "Inspiration/Self-Help" and that description better fits than philosophy or spirituality, despite the expected overlap. Mahler, a writer and media producer by profession, was winter caretaker on a New Mexico ranch, without electricity, with a wood stove and emergency radio. A narrative of this experience would be welcome, and his book is scattered with journal entries, but there are virtually no details nor forthcoming reflections as systematic as Jane Dobisz tells from her winter Zen retreat or the winter solitude of May Sarton. The entries are dropped here and there with no chronology or apparent momentum.

In fact, the content is primarily that of most simplicity and personal time management books, with some historical and anecdotal material added. There are a lot of bulleted lists, such as "Benefits of Silence and Solitude" or "Perceived Advantages and Disadvantages of a Simpler Life," plus quotations, surveys, article-findings like "Symptoms of a Hurry-up World." In the style of a glossy magazine, there are lots of how-to text boxes with recommendations of intended good things to pursue, such as "Exploring the Sensual Pleasures of Silence and Solitude," "Take a Day Off," "Finding Your Natural Place," and "Times and Places to Nurture Silence and Solitude."

Mahler skirts the fence between simplicity and outright solitude, coming down clearly on the side of simplicity as solitude or, maybe, solitude as simplicity, or .... The book lacks a spiritual or even psychological dimension, and without a narrative of his winter of solitude, we have no way to connect his how-to advice with anything other than the popular simplicity books that glut store and library shelves, full of recommended "epicurean" practices to introduce into your daily life.

reviewed 2005

¶