Nicholas of Flue, Hermit of Switzerland

Nicholas

of Flue (1417-1487), also called Nikolaus or Claus von der

Flue) is Switzerland's only canonized saint. He was, as psychologist

Marie Louise Von Franz describes him, "a profoundly introverted,

solitary hermit." The eremitism of Nicholas was a paradox to

contemporaries, but two dimensions of his biography complement his

eremitism, namely a political presence and a mystical persona.

Nicholas

of Flue (1417-1487), also called Nikolaus or Claus von der

Flue) is Switzerland's only canonized saint. He was, as psychologist

Marie Louise Von Franz describes him, "a profoundly introverted,

solitary hermit." The eremitism of Nicholas was a paradox to

contemporaries, but two dimensions of his biography complement his

eremitism, namely a political presence and a mystical persona.

The era of the late Middle Ages was a chaotic time throughout Europe. For Switzerland, the contest of great powers around it was exacerbated by the historical mix of languages and cultures as well as the traditional absence of young Swiss men perennially seeking their fortunes as mercenaries in the wars of neighboring powers. Young Claus spent his youth in such combats, battles identified as Etzel (1439), Zurich (1444), Ragaz (1446), Baar (1446), and the Austrian frontier in Thurgau (1460).

Eventually, Nicholas settled down to marriage with a local peasant girl, also from Sachseln, named Dorothy Wyssling, and they raised 10 children. He continued, however, to take up his soldierly call when summoned, rising to the rank of captain. Son of well-to-do peasants, his piety was common, unexceptional, and predictable -- at this time.

Nicholas was born and lived in the canton of Unterwalden, or Oswalden. Though nearly illiterate and without practical political experience, he was elected or appointed to the town council, then a judgeship, which he held for 9 years. Among his accomplishments in this period was resolution of a dispute between the local parish and the neignoring Engelberg monastery. Nicholas was even offered the governorship of his canton, which he declined.

But his staid life may have led Nicholas to deep reflection. By design, or a vision of God, he one day announced to his family his urgent desire to become a wandering hermit. Nicholas was then about 50.

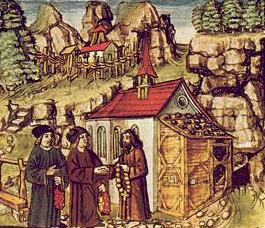

Nicholas declared his intent to travel to foreign lands, but as he walked to Basel, divine inspiration bid him stop and take up residence in Ranft, about an hour's walk from his home. Here he built a crude hut, refusing winter clothing for a mere gown, and refusing food and drink for nearly two decades ("confirmed" by civil and ecclesiastical authorities over the years). He now called himself "Brother Klaus." When a dangerous fire in the nearby town of Sarnen miraculously extinguished itself, the prayers of Nicholas were credited. His fame began to spread. Civil authorities built a cell and chapel for him, the latter dedicated by vicar-general and bishop of Constance. After the pope granted an indulgence for pilgrimage to his hermitage, visitors from throughout Europe streamed to Nicholas' quarters seeking counsel, both personal and political. The Ranft location was declared to be on the route to the pilgrim shrine of Santiago de Compostela in Spain, and designated part of the Way of St. James, or Jakobsweg.

A famous illustrative incident

in Nicholas' political career

occurred in 1480, when Swiss delegates attending the Diet of

Stans

threatened one

another with dissolution of the confederacy. The animosity pitted rural

and urban Swiss. The pastor of Stans hastened

to Nicholas, begging his intervention. But Nicholas had vowed to never

leave his cell. Instead he entrusted a simple statement to the pastor,

urging a peaceful settlement of the issues, with a few modest

propositions. The pastor hurried back to Stans, and the delegates

heeded Nicholas' advice, thus averting disasterous civil war. Though

the content of

Nicholas' advice was never publicized, letters of thanks from the

cities of

Berne and Soleure survive, as well as illustrative plates in

the

Amtliche Luzerner Chronik illustrated by Diebold Schllling the Younger

in 1513. These documents attest to the esteem in which Nichols was

held. Thus Nicholas became what Von Franz calls the "political savior

of Switzerland."

A famous illustrative incident

in Nicholas' political career

occurred in 1480, when Swiss delegates attending the Diet of

Stans

threatened one

another with dissolution of the confederacy. The animosity pitted rural

and urban Swiss. The pastor of Stans hastened

to Nicholas, begging his intervention. But Nicholas had vowed to never

leave his cell. Instead he entrusted a simple statement to the pastor,

urging a peaceful settlement of the issues, with a few modest

propositions. The pastor hurried back to Stans, and the delegates

heeded Nicholas' advice, thus averting disasterous civil war. Though

the content of

Nicholas' advice was never publicized, letters of thanks from the

cities of

Berne and Soleure survive, as well as illustrative plates in

the

Amtliche Luzerner Chronik illustrated by Diebold Schllling the Younger

in 1513. These documents attest to the esteem in which Nichols was

held. Thus Nicholas became what Von Franz calls the "political savior

of Switzerland."

Though Nicholas left his family (however wealthy enough to sustain itself) to become a hermit, he is nevertheless was to be esteemed a patron of peasant families, rural communities, and land stewardship.

Mystical hermit

Popularizations of the life of Nicholas of Flue conflate his influence on contemporary events with his mysticism. Through his hermit life, Nicholas experienced visions, vividly recalled. When still with his family and considering an eremitic life, Nicholas had dreamed of a horse consuming a lily, which he took to mean that the cares of the world (represented by the draft-horse) were consuming the spiritual life (represented by the lily). A significant dream justified his eremitic life, wherein he sees a pilgrim approaching him, who is transformed into Christ but also Wotan, and into a berserker, a wildman in appearance, like a bear, frightening in aspect. C. G. Jung interpreted the dream carefully and explicitly:

The meaning of the vision could be this. Brother Klaus recognizes himself in his spiritual pilgrimhood and in his instinctive (bearlike, i.e., hermitlike) subhumanness as Christ. ... The brutal coldness of feeling that the saint requires to separate himself from woman and child, and friendship is found in the subhuman animal kingdom. Thus the saint casts an animal shadow. He who was capable of bearing in the highest and the lowest to get this is hollowed, holy, whole. The vision is telling him that the spiritual pilgrim and the berserker are both Christ, and this paves the way in him for forgiveness of the greatest sin, which is sainthood.

To be a saint, in the eyes of Nicholas and the world, was a "sin" in that it required a turning away from filial affection, from family duty, from love of his spouse to whom he was jointed in sacramental union and therefore obliged to care for. But sainthood calls for removing all of this human accretion, nd so he has taken this dangerous psychological step. The dream reassures him

As Von Franz explains, the vision of Brother Klaus "unites irreconcilable opposites, that is, subhuman savagery and Christian spirituality." By entering this figure of berserker into his life and psychology, Klaus is capable of reconciling his personal conflicts (and be able to advise anyone else). The eremitic life means reconciling the impulses and instincts of aggression, anger, lust, and pride with the spiritual values of renunciation, disengagement, humility, and non-possession. The Christ-figure has never completely engaged those in the world, never been fully understood as anything but pain nd suffering. Von Franz suggests that only the counterpart berserker figure can provoke the psychic energies that could reconcile the terrible cost of sainthood, could

integrate our personal shadow, not the collective shadow of the Self, the dark side of the Godhead. Yet if we suffer the problem of the opposites to the utmost and accept it into ourselves, we can sometimes become a place in which the divine opposites can spontaneously come together. This is quite clearly what happened to Brother Klaus.

The bear-skinned pilgrim who is the berserker is also the bear who has attained the honey of love and compassion, who can advise and sympathize with others while retaining his distance. On the personal scale, this attainment allowed Nicholas to feel reconciled to his absence of family life. At the same time opening himself to visitors from many nations and classes. The mature hermit can function like a therapist, as has been seen in hermits throughout history, East and West. Jung went so far as to suggest that Brother Klaus should be the patron saint of psychotherapy.

This famous vision exemplifies Jung's comment that Brother Klaus' dreams and visions are largely unadulterated by formal learning other than rudimentary catechetical knowledge of the time. The dreams and visions clearly represent universal archetypes. Thus the famous wheel image found on the cell wall of Brother Klaus' hermitage in his last year of life, and reportedly described by him as "my book in which I learn and seek the art of its teaching."

But the image was a

remnant of a dream he experienced 10 years before his death, the vision

of an angry and terrible God, with six images representing six episodes

in the life of Christ -- as well as six religious virtues enjoined by

the mollifying words of Jesus -- again reconciling the psychological

opposites represented in Christianity.

But the image was a

remnant of a dream he experienced 10 years before his death, the vision

of an angry and terrible God, with six images representing six episodes

in the life of Christ -- as well as six religious virtues enjoined by

the mollifying words of Jesus -- again reconciling the psychological

opposites represented in Christianity.

Conclusion

As Von Franz notes, " compared to such holy sages as Lao Tzu or Chuang Tzu, Brother Klaus as a solitary hermit is a humbler figure." The identification of eremitic solitude as a vocation not only exempted him in the eyes of his Swiss compatriots as a gifted person, but gave Brother Klaus the psychological space to grow as a hermit reconciling the opposing needs of spirituality and sociability, of mystical vision and contribution to others. His abandonment of the world was an abandonment of its false values, but not of his fellow human beings in their simple yearnings.

Nicholas of Flue is esteemed by Christians of many sects. The Swiss Protestant writer Denis de Rougemont wrote a play about the life of Nicholas, and it was set as a libretto to an oratorio by the Protestant Swiss composer Arthur Honegger in 1939. The work was performed in Rome on the canonization of Nicholas of Flue in 1947.

¶

BIBLIOGRAPHICAL REFERENCES

Basic information about Nicholas von Flue is readily available, especially in German. Virtually the only popularization in English is decades old (G. R. Lamb: Brother Nicholas; New York: Sheed and Ward, 1955), attesting to lack of interest outside German-speaking areas. Sources focusing on eremitism and mysticism include C. G. Jung: "Bruder Klaus," in Jung's Collected Works, v. 11, p. 474-487; New York: Pantheon, 1958, and Maria-Louise von Franz: Die Visionen des Niklaus von Flüe. Einsiedelin, Switzerland: Daimon, 1980 (not translated into English) and her "The Transformed Berserker: Union of Opposites" in Archetypal Dimensions of the Psyche; Boston: Shambhala, 1999.